The Bloody Angle

Robert Clotworthy Allen was born June 22, 1834 in Virginia and graduated from the Virginia Military Institute. He became a lawyer before the war. He began the Civil War as major of the 28th Virginia Infantry, but was promoted to colonel of the regiment less than a year later. He was captured at Williamsburg, but managed to escape and was then wounded in action at Gaines' Mill outside of Richmond. Coming to Gettysburg, Allen's regiment was a part of Richard Brooke Garnett's Virginia Brigade in Pickett's Division. During Pickett's Charge, the color-bearer of the 28th Virginia was shot. Colonel Allen picked up the colors and began to advance just a few paces from the stonewall when he too was shot in the head. He and his brigade commander Eppa Hunton had a disagreement at 2nd Manassas the year before when Allen halted his regiment after being ordered to advance. Hunton had regretted that he had not court-martialed Allen at the time. Many of Allen's men thought he was too strict as a commander and disliked him. Nevertheless, he will be remembered today for his bravery at Gettysburg. He was 30 years old. His remains were buried in a mass grave and probably rest today in Richmond's Hollywood Cemetery.

Colonel William Dabney Stuart

William Dabney Stuart was born on September 30, 1830 in Virginia. He too graduated from the Virginia Military Institute and taught there for three years. He began the Civil War as a First Lieutenant. He soon was made Lieutenant Colonel of the 15th Virginia Infantry during the summer of 1861. By the fall, he was elected colonel of the 56th Virginia Infantry. His brigade formed a part of Richard Garnett's Virginia Brigade also. He was a distant cousin of Jeb Stuart. During Pickett's Charge, Stuart yelled, "See that wall there! It's full of Yankee's! I want you to take it!" He was hit in the abdomen soon after and was carried back to his home in Virginia where he would die by the end of the month. He was 32 years old. He rests today in Thornrose Cemetery in Staunton, Virginia.

Lewis Burwell Williams, Jr. was born on September 13, 1833 in Virginia. He too graduated from the Virginia Military Institute and taught there briefly before becoming a lawyer. He began the war as a captain and worked his way up to colonel of the 1st Virginia Infantry. He was wounded and captured at Williamsburg, but soon was exchanged. At Gettysburg, Williams regiment was a part of James Kemper's Virginia Brigade in Pickett's Division. Like General Garnett, he was too sick to walk and received permission to ride his horse during the charge. Closing on the stonewall, an artillery round exploded overhead which threw him from his horse. He crashed to the ground, falling on his sword and would die two days later. He was 29 years old. He rests today in Hollywood Cemetery alongside his men.

Colonel Waller Tazewell Patton

Waller Tazewell Patton was born on July 15, 1835 in Virginia. He too was a graduate of V.M.I. and had briefly taught there. He then became an attorney and the captain of a militia company. When the war began he worked his way up through the ranks to become colonel of the 7th Virginia Infantry. He was slightly wounded in the hand at Second Manassas. At Gettysburg, his regiment served as a part of Kemper's Brigade in Pickett's Division. He'd been elected to the Virginia legislature, but refused to take his seat because he wanted to remain with his men in the army. During the assault called "Pickett's Charge" he had his jaw ripped away by artillery fire. He would die seventeen days later in a Federal field hospital. He was 28 years old. He rests today in the Stonewall Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia. His brother's grandson would become famous in World War II. His name was General George Patton.

James Gregory Hodges was born in 1829 in Virginia. He became a pre-war physician, mayor, and militia colonel. His regiment seized the Norfolk Navy Yard as soon as Virginia left the Union. He soon became colonel of the 14th Virginia Infantry. He was wounded at Malvern Hill by artillery fire. His regiment was part of Lewis Armistead's Virginia Brigade in Pickett's Division. He was killed instantly during the attack within feet of the "bloody angle." He was 33 years old. He probably rests in Hollywood Cemetery with his men. There is a marker for him in Cedar Grove Cemetery in Portsmouth, Virginia, although it is doubtful he is buried there. He was most likely buried in a mass grave near the stonewall.

Colonel Edward Claxton Edmonds

A portrait of Edward Claxton Edmonds

Edward Claxton Edmonds was born in 1835 in Virginia. He too graduated from V.M.I. and became a principal of a military academy. When the war began he was elected colonel of the 38th Virginia Infantry. He was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines. His regiment was a part of Armistead's Brigade of Pickett's Division. As he reached a position just thirty feet from the stonewall, he was killed. Initially buried on the field, his remains most likely rest with his men in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. Edmonds was 28 years old.

John Bowie Magruder (not to be confused with Confederate General John Bankhead Magruder) was born in 1839 in Virginia. He graduated from the University of Virginia and became a school teacher. In 1861, with the war looming on the horizon, he briefly studied tactics at V.M.I. He worked his way up from captain to colonel of the 57th Virginia Infantry. At Gettysburg, his regiment was also a part of Armistead's Brigade. As he led his regiment toward the "bloody angle" he pointed to Cushing's artillery pieces and yelled, "They are ours!" He was then shot in the left breast within twenty yards of the stonewall. Moments later another bullet struck him in the arm passing sideways through his body. He would die two days later in a Federal field hospital and buried on the field. His northern fraternity brothers would soon recover his remains and send them south for burial. He was 23 years old. He rests today at his home called "Glenmore" just seven miles outside of Charlottesville, Virginia.

Colonel Hugh Reid Miller

Hugh Reid Miller was born in 1812 in South Carolina. He would graduate from the University of South Carolina. He then moved to Mississippi where he would become a lawyer, judge, and politician. He helped raise a company at the beginning of the war. He became colonel of the 42nd Mississippi Infantry. At Gettysburg, his regiment was a part of Joseph Davis's Mississippi Brigade of Heth's Division. He survived the heavy fighting on the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg. His regiment was called upon to fight once more during what came to be known as Pickett's Charge. Advancing with his regiment, he was struck in the chest at a fence near the Federal line (probably the fence bordering both sides of the Emmitsburg Road. His son allowed himself to be captured by the Federals just so he could be by his fathers side. Lee asked Meade about Miller's condition (one of the few communications between the two army commanders at Gettysburg). Miller died sixteen days later in a private home in Gettysburg. His son asked and received permission to bring his father's remains back south for burial. Hugh Miller was 51 years old. He rests today in Odd Fellows Cemetery in Aberdeen, Mississippi. Me and my buddy Jerry Smith have visited this cemetery a few years ago, but unfortunately, I don't think we saw Colonel Miller's grave, not having known about him until now.

Colonel James Keith Marshall

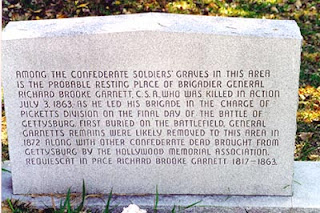

James Keith Marshall was born in 1839 in Virginia. He too graduated from V.M.I. and became a teacher in North Carolina. He began the war as a captain in the 1st North Carolina Infantry. He eventually became colonel of the 52nd North Carolina Infantry. This unit arrived at Gettysburg as a part of Pettigrew's North Carolina Brigade in Heth's Division. When General Heth (pronounced Heath) was wounded by artillery fire on the first day of battle, Pettigrew was placed in command of the division. This put Pettigrew's North Carolina Brigade under the able command of James Keith Marshall. Despite the brigade having suffered 1,100 casualties out of 2,584 men on the first day of battle, they were ordered to participate in "Pickett's Charge" on the third and final day. As he led the brigade past the Emmitsburg Road, he turned to General Heth's son and said, "We do not know which of us is to fall next." Moments later as his brigade neared the stonewall, Colonel Marshall was struck in the forehead by two bullets and killed instantly. He was buried on the battlefield and probably removed to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia along with his men after the war. He was 24 years old.

This ends my three part blog on the colonel's of Gettysburg and I hope everyone enjoyed the brief bio on these brave men.