Thomas Muldrop Logan

Thomas Muldrop Logan was a long lanky Confederate Brigadier General by the end of the war. He was born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1840. He graduated first in the South Carolina College in 1860 and began the war as a private. Following the bombardment of Fort Sumter, he was elected 1st lieutenant in the Hampton Legion. He saw his second serious action at the Battle of Manassas on Henry Hill. He action there won him a promotion to captain.

During the Seven Days battles, he was severely wounded at Gaines Mill and put out of action a few months. Though not quite healed yet, he returned in time to fight at Second Manassas. The Hampton Legion overran an artillery battery there and he won even more praise for his performance. At Sharpsburg (Antietam) he won even more praise for his distinguished bravery.

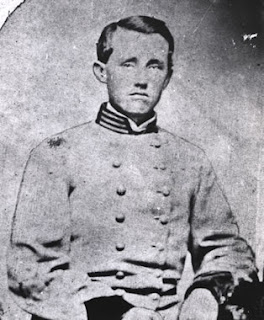

The Boyish Looking Thomas Logan

Following that battle, he transferred to Micah Jenkins South Carolina Brigade as a lieutenant colonel. He was praised in that capacity as well. Along with the rest of Micah Jenkins men, he missed the Battle of Gettysburg. At the Battle of Chickamauga, he was placed in charge of all the sharpshooters in John Bell Hood's division. He continued in that capacity to the Battle of Knoxville where Longstreet praised him for his courage and skill.

Logan was then sent to Drewry's Bluff where he served Beauregard as a staff officer. Following an engagement there, he won promotion to colonel and was given command of the famous Hampton Legion. There were two Hampton Legion's at this time, one of infantry and one of cavalry. Logan commanded the cavalry regiment. He saw action at Riddell's Shop where he suffered another serious wound.

After he recovered, he was assigned to command Butler's South Carolina Cavalry Brigade. Fitz Lee recommended he be promoted to brigadier general and permanently assigned to that command. His promotion to brigadier general ranked from February 15, 1865. At the time, he was the youngest general in the Confederate Army. He saw action at Bentonville as a general and the war came to a close.

One of only three photographs of Logan in uniform

During the surrender ceremonies, Sherman met Thomas Logan and could hardly believe that such a "slight, fair haired boy" was a general. He imagined that Logan must be the youngest general in the war. He of course was wrong, that distinction belonged to Union Brigadier General Galusha Pennypacker who was four years younger than Logan. (Legend sometimes has it that Pennypacker was promoted by Lincoln because he thought his last name sounded comical.)

General Logan asked Sherman if he could take the train home to Charleston, South Carolina. Sherman surprised him by offering him a seat on the train about to leave for Raleigh. Logan was surprised by the kindness of Sherman, but replied that he wasn't ready to leave just yet. He wanted to say goodbye to his men. Sherman told him to just find General Kilpatrick when he was ready to go and he would direct him to Sherman who would ensure he had a seat on a train. Logan thanked Sherman for his kindness.

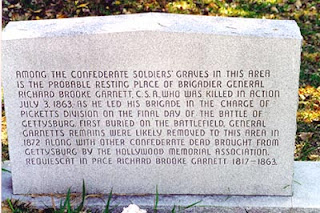

Kate Virginia Cox

Following the war, Thomas Logan borrowed five dollars and married Kate Virginia Cox of Virginia. He studied law in Richmond and soon became a railroad tycoon. He was one of the lucky ex-Confederates that didn't struggle to make a living. He was often associated with John D. Rockefeller. He died in New York City in 1914 and is buried in Hollywood Cemetery, the "Arlington of the Confederacy" in Richmond, Virginia.

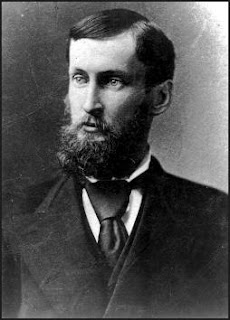

A post-war photograph of Thomas M. Logan

My buddy Jerry (right) and I at the grave of Thomas M. Logan