Joshua Woodrow Sill

Joshua Woodrow Sill was born in 1831 in Chillicothe, Ohio. His father was an attorney who obtained the young Sill and appointment to West Point. He was quite an academic student, managing to finish third in a class of 52 cadets. Because of his high rank, he was able to earn an assignment in the ordnance department and was stationed in New York. Later, he was assigned an instructor at the United States Military Academy.

Just as the Civil War was breaking out, he resigned his commission to become a college professor. When the South opened fire on Fort Sumter, Sill resigned his position and offered his services to the state of Ohio. He was commissioned colonel of the 33rd Ohio Infantry Regiment.

He saw little action before being promoted to brigadier general in Phil Sheridan’s division. He and Sheridan became best friends during the time he commanded the brigade. His first major engagement was at the Battle of Stones’ River, called the Battle of Murfreesboro by the Confederate troops.

Philip Sheridan

The day before the battle opened, Sheridan called a conference with his brigade commanders. When the conference ended, Sill mistakenly put on Sheridan’s coat and Sheridan put on Sill’s coat. Thus during the battle of the next day, both men were wearing the others coat.

The Confederates struck Sheridan’s part of the battle line about 7:15 the next morning. The Southern troops charged right up to the muzzles of the Federal guns before breaking. Sill’s men in turn charged the retreating Confederate troops. Sill charged forward with his men and fell dead, a bullet passing through his upper lip and lodging somewhere in his brain. He was wearing Sheridan’s coat at the time of his death.

The Confederate troops were extremely proud of having killed Joshua Sill. He had allegedly committed numerous acts of cruelty on the women, children and old men behind Federal lines just days before the battle. Confederate General Braxton Bragg stated that Sill’s body was captured and decently buried in the town of Murfreesboro which was more than the man deserved.

According to Federal soldiers, Joshua Sill was loved, admired, and respected more than any other officer in the army. Sheridan later named a fort in Oklahoma after Joshua Sill. Fort Sill is still the largest Artillery depot in the world.

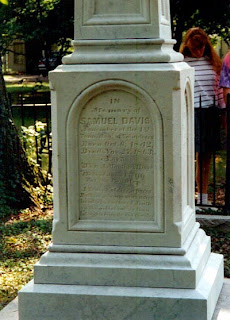

Monument to Sill located at Fort Sill in Oklahoma

Joshua Sill was later removed from Murfreesboro and today rests in Grandview Cemetery, Chillicothe, Ohio. He was thirty-one years old.

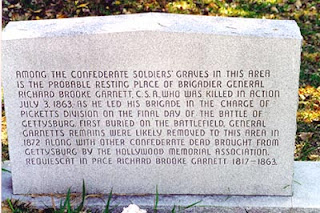

Joshua Sill's gravesite