The Confederate Battle Flag

St. Andrew's Cross Flag

I've already written a blog on the Confederate Battle Flag being based on the Christian flag of St. Andrew, one of Jesus's Apostles and the younger brother of Peter. I won't repeat what I've already stated as you can go back and read those blogs if you're interested. I'm going in a different direction with this blog. Legend has it that Andrew was crucified on an "X" shaped cross different from the type that Christ was placed upon. The St. Andrew's Cross flag was derived from this legend. The flag has Christian origins. So the question arises, "How did a Christian flag come to be viewed as racist?"

I've already told the story of the flag used by the KKK in the early 1900's. Below is a photograph of the 1928 Klan march on our nation's capital. You won't notice any Confederate Battle Flags in the photograph, but the U.S. National Flag. I've already asked why we don't consider that flag racist, but have yet to receive an answer from people that worship that flag while calling for the abandonment of the Confederate Battle Flag.

1928 Klan march on Washington, D.C.

I recently listened to a talk given by a friend of mine who happened to serve on the grand jury hearings for the case of the 16th Street Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama on September 15, 1963 in which four young black girls were killed. I won't mention my friends name here because I have not received prior permission from him. I will explain what he learned from being on the grand jury.

First off, he learned why the Klan began to use the Confederate Battle Flag as its official symbol and turns out, it's the same reason other people use the flag. It has nothing to do with the Confederacy being a slave holding nation at all. When the protests began in earnest across the South to stop segregation, the Klan at that time was a peaceful organization or at least most of it's members attempted to be peaceful. Some of the younger members decided it was time for more radical action and appealed to the older Klan members for violence. The older members naturally didn't agree with this approach. The younger members fed up with what they considered the inaction of the older members did what they thought was right. They naturally raised the Confederate Battle Flag in defiance (that flag is the international symbol of defiance of course) in protest of the old leadership. Why else would the Confederate Battle Flag be displayed in Crimea during it's secession from Ukraine? There are almost no blacks there, so obviously, they aren't attempting to downgrade that race. It's become the international symbol of defiance to an overreaching authority.

Another thing that I learned from my friend on the grand jury trial that I'd never heard before was the fact that no one was supposed to be killed in the bombing at the church. The bomb was placed the night before and supposed to explode during the night. These Klan members didn't know how to correctly build a timer on their bomb. By the next morning when the bomb was supposed to have already exploded, none of these guys had the courage to walk up and see why it hadn't gone off yet. Unfortunately, for all involved, the bomb went off at the worst possible moment.

A Russian lady protesting with a non-Russian flag

Now let's move on to the ignorance our nation teaches. Because most of our nations lawmakers are unfortunately lawyers and they just want to "kiss ass" for a vote, none of them have the backbone to stand up for what is right. They jump on the bandwagon of "political correctness" and sing along. So, here are a few observations that should shake the politically correct to the core.

In an attempt to do away with the Confederate Battle Flag on Georgia's state flag, the politically correct raised enough protest to have the flag changed. The flag was changed from a battle flag that never flew over a slave holding nation to one that looks almost identical to the Confederate First National flag and a nation that did hold slaves.

The Confederate 1st National Flag or "Stars and Bars"

The modern day Georgia state flag is not considered racist, but can you see any resemblence?

Even funnier for me is the fact that none of the people that protest these things are smart enough to figure any of it out for themselves. Let's take a look at the march President Obama led across the Edmund Winston Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama on March 7, 2015. Below you can see a photograph of him on the bridge, but behind him is the obvious name of the bridge.

Obama and others on Edmund Winston Pettus Bridge in Selma

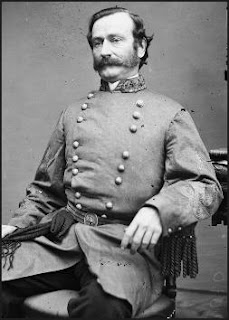

Why do I think the above photograph is comical? For starters, the bridge is named after Brigadier General Edmund Winston Pettus, a Confederate Brigadier General, and later a member of the original Ku Klux Klan. Now it's not funny that he is standing in front of a name associated with the Klan, because anyone one that care's to learn the true history of our nation will readily admit that the original Klan was meant to drive out the carpet bagger's from up North. They were not a racist group at all. The funny thing to me is the fact that no one in America realized who the bridge was named after until days after the photograph was taken. No one on Obama's staff even knew who General Pettus was. General Pettus was a great man, not a racist person at all. He loved the South and fought hard against the Central Government of Lincoln. He joined the Klan because he lived in a land where Southern white males had no representation in the government. He is buried beneath a flat marker (nothing fancy at all) because he was an extremely humble person. Now we learn that the politically correct want to rename the bridge after having been told who the bridge was named after. This I find extremely funny.

Reminds me of a quote attributed to one of the South's arch enemies, Abraham Lincoln said, "You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time." Maybe he should of been alive today to see how "dumbed down" we've become.

So what is the best way to take this flag back from the Klan and the skinheads? There is a simple solution. The black race needs to stop protesting this flag and embrace it. After all, as Frederick Douglass once stated, the black race is the stomach of the rebellion. Whether or not you believe blacks fought for the South, you must admit the South couldn't have survived without the help of the black race just as Frederick Douglass understood. Why then should the black race hate that flag?