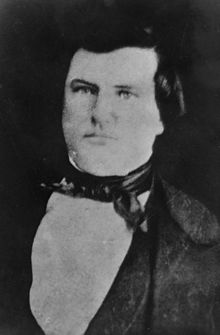

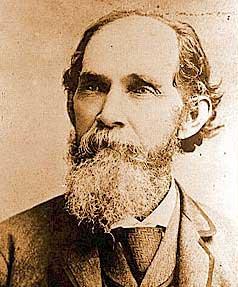

Major General John A. Wharton

Most people don't understand why people in the South are considered so much more respectful than Northerners. There is a reason for this and it goes way back beyond the Civil War. In the South, there was a code of honor among gentlemen. If you insulted a man, you may find yourself challenged to a duel. I've already written a blog on dueling in the old South if you'd like to read it. http://trrcobb.blogspot.com/2013/05/antebellum-dueling.html There were rules that were supposed to be followed. I read an article a couple of years ago about newspaper editors in the antebellum South. You'll have to forgive my memory, but I remember being amazed at the number of times the average editor was challenged to a duel during his lifetime for something printed in his paper.

The most famous duel of the war is the one that occurred between Missouri Major General John S. Marmaduke and Tennessee Brigadier General Lucius Marshall Walker near Little Rock, Arkansas. Marmaduke accused Walker of cowardice and they met at dawn one morning despite orders to refrain from dueling. When it was over, Walker lay dead, never to be called a coward again. The other famous duel of the war occurred earlier in the war when Major Alfred Rhett killed his commanding officer Colonel William R. Calhoun (nephew of John C. Calhoun).

Major Wharton wouldn't have the opportunity to defend himself in a duel. Born in Nashville, Tennessee, the Wharton family moved to Texas while he was young. He was described as a "red-haired, freckle-faced boy." John Wharton graduated from the University of South Carolina in 1850. While in that state, he married the daughter of Governor David Johnson. Upon graduation, Wharton returned to Texas where he practiced law. He soon made enough money to purchase a plantation. He was a strong supporter of secession.

When the war began, he and other Texans headed to Richmond, Virginia. They saw action at Manasass (Bull Run), but Wharton was sick and missed the battle. He then became a captain in the 8th Texas Cavalry. The unit became known as "Terry's Texas Rangers". Colonel Benjamin F. Terry was mortally wounded at Rowlett's Station and his successor Thomas S. Lubbock became sick and died. John was promoted to colonel of the regiment.

At Shiloh, Wharton was wounded, yet he refused to leave the field. He remained in command and helped cover the retreat of the army to Corinth. General William J. Hardee called him "the gallant Wharton." This praise helped stoke the fires of military ambition in Colonel Wharton. He was then placed under command of Bedford Forrest and fought in an engagement at Murfreesboro on July 13, 1862. Forrest commended him for moving forward at the head of his command. He was severely wounded in this assault.

Wharton recovered in time to lead his regiment during Bragg's Kentucky invasion. He had a horse shot from beneath him at Bardstown and at Perryville he was praised for leading one of the greatest charges of the war. Because of this, he was promoted to brigadier general on November 18, 1862.

John Wharton received command of a two-thousand man brigade and joined Joseph Wheeler's cavalry. He was praised by Wheeler and received promotion to major general on November 10, 1863. He continued to serve under Wheeler in the action around Chattanooga. Rumors began to circulate that Wharton was a superior general to Wheeler. These rumors soon reached Wheeler's ears and Wheeler immediately began to complain to General Joseph Johnston about his subordinate. Wheeler stated that ambition had turned Wharton into a "frontier political trickster."

Johnston understood something must be done to retain peace among his commanders. Wharton had applied to President Jefferson Davis for a transfer to the Trans-Mississippi (area west of the Mississippi River) and Johnston realized this would solve his problem. Wharton was ordered to report to Edmund Kirby Smith in Texas.

He arrived there in the spring of 1864 and when General Thomas Green was killed at Blair's Landing, he took command of Richard Taylor's cavalry in Louisiana. Taylor praised his performance, but the Trans-Mississippi didn't receive the attention of the army's east of the river. He soon applied for a return to Johnston's army in Georgia. That transfer regrettably would never occur and John Wharton would die as a result.

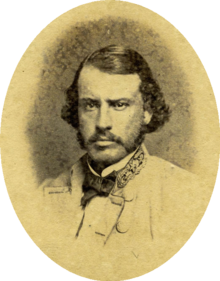

Fellow Texan Colonel George Wythe Baylor (brother of Colonel John R. Baylor the famed Indian fighter) and John Wharton would have problems. Baylor had served on General Albert Sidney Johnston's staff at Shiloh. Both men were ardent Texans devoted to the Confederate cause. Deep down, they were very different men. Baylor was a self-made man who'd worked hard all his life for what he'd obtained. Wharton was born to wealth and education. More trouble was brewing than just their backgrounds.

The first incident between the two men occurred when Colonel Baylor on furlough applied for an extension because of his wife's ill health. Wharton had denied the furlough writing, "I know nothing of Mrs. Baylor's health. Colonel Baylor is needed with his regiment." Baylor believed that Wharton was calling him a liar to have his furlough extended.

Most people saw Wharton as a future politician careful to look for future votes. Like a true politician, most felt he took care of his friends at the expense of others. General John B. Magruder placed Baylor's cavalry under Wharton's command and soon after asked Wharton for troops to serve as dismounted cavalry. Wharton immediately sent him Baylor's men. This infuriated Baylor. According to Baylor (he'd been commanding a cavalry brigade for some time), Wharton had promised him a promotion to brigadier general and now was forcing him to serve under a lower ranking officer as infantry. For Baylor, it was just too much.

Colonel George Wythe Baylor

The sad part of the episode is the fact that Baylor was placed under a general who wasn't able to take the field which basically ensured him an independent command. Wharton probably saw it in this light. Baylor's pride was hurt and that fact didn't make him feel any better. In his defense, by this point of the war, Baylor was himself in poor health. He'd been suffering from dysentery and had lost a lot of weight. Despite standing six feet, two inches he weighed less than 140 pounds. His brother John R. Baylor was known for his fiery temper and Baylor probably wasn't much better.

Wharton didn't help the situation with his language. He was famous for cursing when speaking to his subordinates and talking harshly when he did address them. Things were quickly coming to a climax between the two men. On the morning of April 6, 1865 (just three days before Lee surrendered at Appomattox), both General Wharton and General James Harrison came riding into Houston in a carriage to visit their superior officer Major General John B. Magruder.

Colonel Baylor was in town that morning attempting to enlist the help of General Walter Paye Lane in getting his orders countermanded. Lane refused to get involved (especially after the reports of the way Wharton talked to his subordinates). Having failed to receive any help from Lane, Baylor strolled through town with Captain Sorrel. Wharton, riding in the carriage spotted Baylor and dressed him down for being absent from his command. It had to be an embarrassing moment for Baylor being "chewed out" in front of Captain Sorrel and General Harrison. Baylor informed Wharton that it was imperative that he be in Houston to have his men removed from the situation they were in or they would all desert. He then told Wharton he was going to see Magruder to complain about Wharton. The situation began to escalate and both men's voices began to rise. Wharton demanded to know when he'd ever treated Baylor unfairly. Baylor named several instances that in his mind were mistreatment.

Wharton called Baylor a "damned liar." In the old South calling someone a liar was just asking to be challenged to a duel. Baylor then called Wharton a "liar" and stepped toward the buggy with his hand raised. General Harrison shocked at the escalating situation nudged the horse forward. Baylor shouted, "Stop the buggy, sir!" Harrison ignored him. The buggy continued down the street with Baylor still shouting at Wharton.

Later that afternoon, Wharton and Harrison arrived at Magruder's hotel room to find his commander absent, but Colonel Baylor sitting on his bed awaiting his return. Wharton began to shout at Baylor about his earlier insubordination. Harrison attempted to intervene, but things were out of control. Wharton struck Baylor in the face (Baylor claimed he was punched with a fist, but some say it was an open-handed slap) before Baylor drew his revolver. Harrison was still attempting to get both men under control when Baylor fired under his outstretched arm hitting Wharton in the chest. Wharton was dead when he hit the floor. General Harrison then grabbed Baylor and said, "Colonel, he was totally unarmed!" Baylor simply turned and left the building. He would never be punished.

Unlike in a duel, Baylor had killed an unarmed man. In that time period, this would be construed almost like an act of cowardice. Wharton was 36 years old and rests today in the Texas State Cemetery, Austin, Texas. George Baylor would become a post-war Texas Ranger, writer, and serve in the Texas state legislature. He died on March 24, 1916 and rests today in the Confederate Cemetery, San Antonio, Texas. He was 83 years old. Baylor claimed that he regretted killing General Wharton for the remainder of his life calling it a "lifelong sorrow." Those closest to Baylor reported that he couldn't mention the entire affair without coming to tears. He stated, "I trust everyone who knows me personally will believe me when I say the whole thing was a matter of sorrow and regret to me." Baylor is remembered as a military commander as "a courageous individual fighter...lacked reserve, was a poor disciplinarian, and an indifferent judge of men." Both men are remembered for their fearlessness in combat. Wharton is remembered as a fine combat commander.

George W. Baylor later in life