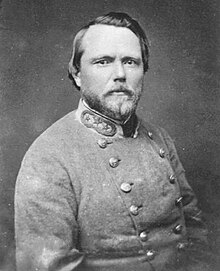

Brigadier General Samuel Garland, Jr.

Samuel Garland, Jr. was born on December 16, 1830 in Lynchburg, Virginia. He graduated second in his class at V.M.I. in 1849. Prior to the Civil War, he became a lawyer and captain of his local militia company. In 1856, he married Elizabeth Campbell Meem. He purchased a home for Eliza as she was called in Lynchburg.

Home of Samuel and Eliza Garland

When the war began, Garland became colonel of the 11th Virginia Infantry. His regiment was assigned to Longstreet's Brigade near Manassas, Virginia. On June 12, 1861, Eliza would die of the flu and was buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery in Lynchburg, Virginia. Garland saw action at the engagement at Blackburn's Ford and was praised by General Longstreet for his coolness. The regiment would be held in reserve during the Battle of Manassas. On July 31, 1861, Garland's four year old son Sammie would also succumb to the flu. He was buried next to his mother in Lynchburg. Samuel Garland was devastated, but because of his religious beliefs he knew he would meet them again. He would be somewhat depressed for the rest of his life.

He led his regiment again in the skirmish at Dranesville and was praised for his coolness in action there. Joseph Johnston recommended he be promoted to brigadier general for his bravery under fire.

His regiment was assigned to D.H. Hill's Brigade at the Battle of Williamsburg and earned praise from Hill when he was wounded, but refused to leave the field. Because of this action, he was promoted to brigadier general on May 23, 1862 and given a brigade. He had two horses shot from beneath him in the Battle of Seven Pines.

During the Battle of Gaines' Mill, he successfully attacked a Federal flank and his brigade took many prisoners. He also led his brigade in the slaughter at the Battle of Malvern Hill. General Garland's reputation was outstanding by this point and he seemed destined for higher command.

Samuel Garland in his militia uniform before the war

General Garland's brigade was assigned to guard Richmond and Fredericksburg which ensured his missing the Battle of Second Manassas. His brigade was still a part of D.H. Hill's Division during the Maryland Campaign. His brigade contained a little over one thousand men during the Battle of Fox's Gap on South Mountain just two days before the Battle of Antietam.

As his brigade was being hard pressed there, Colonel Thomas Ruffin of the 13th North Carolina Infantry approached Garland and requested him move back to a safer position. Garland replied, "I may as well be here as yourself."

Ruffin replied, "No it is my duty, but you should lead your brigade from a safer position."

Ruffin was then struck in the hip by a Federal bullet. At the same instant a bullet struck Garland in middle of his back and exited through his right breast. One of his aides rushed forward to his side and caught Garland's last words which were, "I am killed. Send for the senior colonel."

Position marking the spot where Garland was killed at Fox's Gap

General Lee praised Garland as an accomplished and brave officer. His immediate commander D.H. Hill said that Garland was "the most fearless man I ever knew." According to all who served with him, he would have been destined for higher rank had he lived. Samuel Garland was 31 years old. He rests today next to his wife and son in the Presbyterian Cemetery in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Me and Ole Man at the grave of Samuel Garland in Lynchburg