Me being shot in a duel a year ago at LaGrange

If you've read my blog on antebellum dueling written in 2013, your familiar with the photograph above. I had a great time that Saturday getting shot and killed twice in one day. Back during the 1800's, dueling was anything but great fun. Most of the time, one of the men was not walking away. A duel could be issued for any perceived slight. I learned that newspaper editors dueled more than any other person because of something he'd printed that offended someone. Many duels were fought over women. Another thing that would cause a duel would have been to call a man a coward. That was a big "no-no" during that time period.

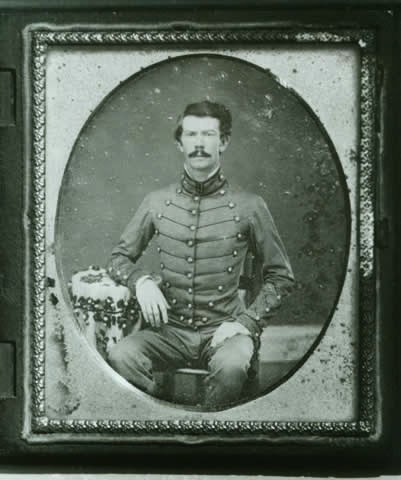

Major General John S. Marmaduke

I remember the first time I mentioned Confederate Major General John Marmaduke to my wife. She burst into laughter and asked, "You mean there was a general named Marmaduke?" I believe she was thinking of the big dog that used to appear in the cartoon section of the newspaper to be the reason she was so amused. Marmaduke was a Trans-Mississippi commander, meaning that he served throughout the war west of the Mississippi River. He was born in Missouri in 1833. He graduated from West Point in 1857, ranked 30th out of 37 cadets. He would become a lieutenant in the U.S. Army serving in the cavalry under Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston. He participated in the Morman expedition before the Civil War began. Although his father wanted him to remain on the side of the Union, Marmaduke resigned his commission to fight for the South. He began the war as a lieutenant, but soon worked his way up to brigadier general.

Brigadier General Lucius Marshall Walker

Major General Lucius Marshall Walker (called Marsh by his friends) was born in Tennessee in 1829. He also graduated from West Point in the year 1850 ranked 15th in a class of 44 cadets. He served on the frontier as a lieutenant until the year 1852 when he resigned and returned to Tennessee to go into business. When the Civil War began, he was living in Arkansas.

He commanded the Confederate forces in a small affair called the Battle of Reed's Bridge or Bayou Meto. The Confederates were forced to retire from their entrenchments, yet halted the Federal advance. After nightfall, the Union forces retreated. General Marmaduke commanded a brigade there under General Walker. He became so incensed at the result of the battle that he asked to be relieved from command under General Walker. He thought Walker had endangered his brigade by retreating after darkness. Walker judged that Marmaduke was calling him a coward and immediately wrote him a letter asking if this were true.

Marmaduke replied to Walker that he had not called him a coward, but that his conduct on the field caused him to no longer want to serve under his command. Major General Sterling Price (their field commander) issued orders for both men to remain with their separate commands. Unfortunately, the order was never delivered to Marsh Walker. General Marmaduke ignored the order.

The letters were exchanged by both officer's seconds, Captain John C. Moore (Marmaduke's friend and second) and Colonel Robert H. Crockett (Walker's friend, second, and also the grandson of Davy Crockett). Both seconds ended up issuing the challenge to the duel without allowing the senior officers to come to their own conclusions. The two general officers met on a Sunday morning, September 6th, on a plantation near Little Rock, Arkansas. Both were armed with Colt Navy Revolvers.

Both men opened fire from fifteen paces and both missed. On the second shot, Walker was hit and collapsed to the ground. Marmaduke immediately rushed to his side and asked how badly he was wounded. Marmaduke then had Walker placed in his own ambulance and rushed to Little Rock to be cared for. Walker died the next day, his bravery now without question. Marmaduke was arrested by General Price, but soon released. Marmaduke would continue the war and become a major general before it ended. In 1884, he would be elected governor of Missouri. He too passed from this earth in 1887. For the rest of his life, he regretted having killed General Marsh Walker.

Me and my buddy James Howard at the grave of Marsh Walker in Memphis, Tennessee