Philip St. George Cocke

Philip St. George Cocke was born in 1809 in Virginia. His father had served as an officer in the War of 1812 and secured Philip with an appointment at the United States Military Academy. He graduated from West Point in 1828, ranking sixth out of forty-five cadets. He would serve in the artillery for six years before resigning to return to Virginia where he would become a planter. He would devote the rest of his life to the management of his plantation in Powhatan County, Virginia and other plantations he owned in Mississippi.

The same year he resigned, he married Sallie Elizabeth Courtney Bowdoin. Cocke became very interested in agriculture and believed in trying new techniques with his crops. As a result, he wrote numerous articles about planting and eventually rose to become president of the Virginia Agricultural Society. He also served on the board of visitors at the Virginia Military Institute.

When Virginia seceded, Cocke was made brigadier general in the Virginia militia and ordered to protect the area just south of the Potomac River. He reported to Robert E. Lee that he had just three hundred men to protect Alexandria, Virginia with against what he thought were over 10,000 enemy troops. Lee implored Cocke to not abandon the town even if it meant fighting against overwhelming numbers. Despite Lee’s pleas, Cocke abandoned the town without a fight.

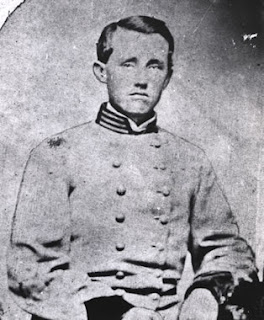

Cocke around the time the war began

Despite this failure in the eyes of Lee, Cocke had studied the terrain around Manassas and it seems he was the first to conceive of that place as the ideal place to make a defensive stand. When Cocke’s troops were merged into the Provisional Army of the Confederate States, he was made a colonel in that army. Cocke was dejected and may have considered resigning, but General Lee must have convinced the man he was needed.

Beauregard took command of the army at Manassas and placed Cocke in command of a brigade. The man saw minor action at Blackburn’s Ford and was praised for leading his brigade into combat during the Battle of Manassas, although his was a minor engagement. After the battle, President Davis promoted Cocke to brigadier general in the Confederate army.

At this point, General Cocke’s life began to spiral downward. He seemed to have been suffering from what would later be called a nervous breakdown. When Eppa Hunton’s regiment was assigned to Cocke’s brigade, he was invited to eat dinner with the man. While he and Cocke rode back to the general’s tent, he suddenly blurted out, “My God, my God, my country!”

This shocked Hunton and he was of the opinion from that moment forward that Cocke’s mind was a little off. The man had been in the field for eight months with huge responsibilities resting on him. Responsibilities that he didn’t seem capable of coping with. A few weeks later he returned home and as one Confederate noted, he was “shattered in body and mind.”

Belmead Plantation

He perceived imaginary slights from General Beauregard on his conduct at the Battle of Manassas. (In fact Beauregard had nothing but praise for Cocke’s performance there.) The man was mentally exhausted having placed too much pressure on himself and his actions. On December 26, 1861, he shot himself in the head at “Belmead” mansion, Powhatan, Virginia and was buried on the grounds there. In 1904, he would be reinterred in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia which is known at “the Arlington of the Confederacy.”

Eppa Hunton may have summed it up best when he had the following to say about General Philip Cocke, “he was a brave man, a good man, an earnest patriot, but he was not a military man.”

Cocke's grave in Hollywood Cemetery