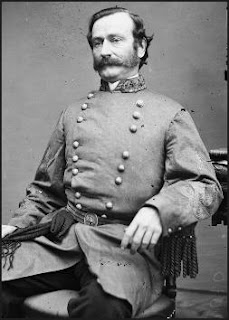

An Early War Photograph of Major General Mansfield Lovell

Most of my blogs are about great Confederate General's that happen to be my hero's. This is not one of those blogs. Mansfield Lovell may have tried his best, but just wasn't a great commander. He was known for his ability with artillery and perhaps in engineering, but he just wasn't a leader of combat troops.

Lovell was born in Washington, D.C. in 1822. His father was the first surgeon general of the United States Army. He grew up in Washington, and after 1836, moved to New York. His grandfather was a prominent politician in Boston, Massachusetts. His ancestry hailed from the north. Lovell received an appointment to West Point and graduated ninth out of 56 cadets in the Class of 1842. His high class ranking ensured he wouldn't be assigned to the infantry and he received an appointment as lieutenant in the artillery. He would see action in the Mexican War, where he was wounded twice and cited for gallantry. Lovell's star was on the rise. For the latter part of the Mexican conflict, Lovell served on the staff of Brigadier General John Quitman.

Brigadier General John Quitman

Quitman, like Lovell was born in the north, studied law, and eventually moved to Natchez, Mississippi. He would become governor of Mississippi from 1850-1851. The relationship between the two men became like a father and son. It is believed that Quitman is the man that swayed Lovell to consider himself a southerner.

In 1854, Lovell resigned his commission from the U.S. Army and moved to New Jersey. He eventually became the deputy street commissioner for New York City under another southerner named Gustavus W. Smith (see my blog http://trrcobb.blogspot.com/2013/07/major-general-gw-smith-was-strain-more.html).

When the Civil War began, both Gustavus Smith and Mansfield Lovell left New York City for the south. They arrived and reported to Joseph Johnston, who in turn recommended them to Jefferson Davis as the two "best officers whose services we can command." Lovell would be sent to New Orleans, Louisiana where he would be promoted to major general and begin service in command of the coastal defenses there.

The Confederate government believed that New Orleans was safe from the south because of Fort's Jackson and St. Phillip. They soon began to strip Lovell of guns and men believing the real threat came from the upper Mississippi River. Six months later, a Federal fleet under David Farragut would run past the forts and capture New Orleans. Lovell received an unfair share of the blame for the loss, but in truth, the government was at fault. Lovell reacted quickly and sent men, guns, and supplies to Vicksburg to hold that important city. Although criticized, Lovell was beginning the war doing the best that could be expected of anyone.

Mansfield Lovell has grown his whiskers out for this photograph

To appease the people of Mississippi and the state government, President Davis placed Major General Earl Van Dorn over Lovell. Van Dorn himself had become something of a failure as a general of troops having almost lost his army at the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern in Arkansas. He assigned Lovell to a division of his new command in Mississippi and marched northward intending to retake Corinth, Mississippi. The Federal commander waiting there was William Rosecrans and ironically, his army was occupying the same breastworks built by the Confederate Army in the spring of 1862.

Lovell began the campaign as a division commander under Van Dorn, but Lovell was an arrogant man. He believed himself superior to Van Dorn and equal to the best general in the Confederate Army. This would be the recipe for a disaster. It was said he had a swagger that reminded his subordinates of a conquering Caesar. To make matters worse, while advancing toward Corinth, he spotted what appeared to be the wheels of a single artillery piece on the horizon. He ordered skirmishers thrown out and an entire brigade to advance across the field toward the enemy threat. The distance was covered quickly, every man expecting to receive enemy fire in an instant. Once the skirmishers reached the position, they found to their amazement, a single pair of abandoned wagon wheels from an old sawmill.

During the first day of the battle, Lovell's division advanced on the far right and after serious fighting took possession of Oliver's Hill. (One of his regiments that my grandfather fought in, was the 35th Alabama Infantry. They captured a cannon there named "The Lady Richardson.") At this point in the battle, Lovell seems to have lost his nerve. With the Federal troops in full retreat, he halted his advance. His three brigade commanders were just itching to finish the fight. Lovell allowed the two divisions on his left to do the remainder of the days work. Brigadier General John Stevens Bowen (see my blog http://trrcobb.blogspot.com/2011/03/death-of-another-stonewall.html) was extremely irritated that the battle had been won when Lovell inexplicably called a halt. He went to Lovell and asked for permission to attack. It was only 3 p.m. For the remainder of the day, Lovell's division cared for their wounded and collected their dead for burial as they listened to the fury of the battle. Lovell's actions are inexcusable.

Another uniformed photograph of Mansfield Lovell

He continued to do little on the second day of the battle. Ordered to attack by Van Dorn, he simply ignored the order and did nothing. Van Dorn must have been out of touch with what was occurring that day because he praised Lovell's actions in his official report. That praise would not save Lovell. President Davis still blamed Lovell for the fall of New Orleans. Jefferson Davis was famous for holding grudges. There were positions where Lovell could have possibly excelled, but Davis refused to give him the chance.

A court of inquiry was held on Lovell's responsibility for losing New Orleans and the court cleared him of any blame. Once this occurred, Joseph Johnston asked Davis to assign Lovell to his army to command a corps. Davis refused. (Likely a good thing considering Lovell's failure commanding troops at Corinth). Again, Braxton Bragg suggested Davis make Lovell chief of artillery of the Army of Tennessee, a position Lovell had excelled in before. Again, Davis refused. The only message from Richmond to Lovell was "Await further orders."

Lovell finally gave up on receiving a new assignment and served Joseph Johnston as a volunteer aide during the Atlanta Campaign. When A.P. Stewart took command of Leonidas Polk's old corps following that officers death, Johnston asked that Lovell be assigned to command Stewart's division. Not surprisingly, Davis refused this request also. Once Hood took command of the army, he asked Davis to assign Lovell to command his old corps. Despite the close relationship between Hood and Davis, the president still would not relent.

Not until Robert E. Lee was made commander in chief of all Confederate troops would Lovell receive another assignment. Johnston was given command of the Army of Tennessee during the Carolina's Campaign in 1865 and asked Lee for Lovell's services. Lee assigned Lovell to command Confederate forces in South Carolina. He held the assignment from April 7 until his surrender one month later.

Lovell's frock coat in the Louisiana State Museum

Following the war, Lovell attempted to run a rice plantation in Savannah, Georgia, but high water wiped out his first crop. He then moved to New York City where he became a civil engineer and surveyor. He helped with the removal of river obstructions in Hell's Gate, Queens, New York. Lovell would die in New York City on June 1, 1884 before the completion of the job. He was 61 years old. He rests today in Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York.

Lovell's grave

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completing the work at Hell's Gate one year after the death of Mansfield Lovell.